Broadband Internet Plans in France

Friday 08 June 2018

The French government has an ambitious plan for all households to have access to 'very-fast' broadband by 2022, but the cracks are already beginning to appear.

According to the ‘Plan France Très Haut Débit 2013-2022 (PFTHD)', the whole of France should have access to broadband speeds of 30Mbps or more by 2022, of which 80% should be supplied by fibre optic to their property.

Additionally, in July 2017 French President Macron announced that he wanted to offer ‘good high-speed’ broadband (at or above 8Mbps) to all households by 2020.

Although over 99% of households in France have access to the internet, only around half are able to avail themselves of broadband of at least 30Mpbs, a flow rate which is regarded by the European Commission as the definition of a very high bandwidth.

This level of coverage for ultra-fast broadband compares poorly with the European average of around 80% of households who have access to at least 30Mbps.

The main problem for France is the low-population density outside urban areas, which makes the installation of très haut débit an uneconomic proposition for telecoms providers.

In order to fill the gaps in rural areas, over the past 15 years successive governments and local councils (communes, departments and regions) have intervened to target those areas where the private sector has been incapable of offering a service.

However, it was not until 2008 that a clearer regulatory, technical and financial framework for the development of high-speed broadband emerged, with much of it to be overseen by the French telecoms regulatory body ARCEP.

Later geographic zoning under initial broadband plans distinguished densely populated areas which were the responsibility of private operators, and less dense areas where the public sector could intervene.

Under the plans, the country has been divided into two main zones; on the one side, 57% of the population who live in dense areas where operators would deploy fibre optic using their own funds; on the other side, the remaining 43% of the population in sparsely populated areas, where local authorities would set up public initiative networks, co-financed with the operators who would build them.

The total estimated cost of the plan was estimated at €20 billion euros, with €7 billion for urban areas and €14 billion for rural areas. Local authorities would be supported to the tune of €3.3 billion in grants by the State, as well as access to cheap loans.

In a decentralised approach, local councils have been encouraged to draw up a strategy for the development of a telecoms in their area, called Schémas Directeurs Territoriaux d'Aménagement Numérique - SDTAN.

There are now many such plans in place, but the adoption of the powers has been far from universal, and implementation has not carried out on a coherent national basis.

There has also been a significant amount of wrangling between the councils and the operators, delays on the release of funds by the State, a dispute with the European Commission on competition grounds, and discord and a lack of coordination between the councils themselves about the development of suitable infrastructures.

It is also questionable whether matters were improved in 2015 when the government established a digital agency called the 'Agence du Numérique', with the aim of galvanizing action, but whose role overlaps with that of ARCEP.

As a result, on the ground the picture has been a very confusing one, with many different actors, both public and private and joint, intervening to establish local infrastructures that have been unevenly provided.

In 2017 the French national auditor, the Cour de Comptes, also cast doubt on the 2022 target for 100% very-fast broadband, considering 2030 a more realistic date, whilst also considering that there was a funding shortfall of around €15b. Other commentators have made the same observations.

Nevertheless, the government has persisted with the plan, using with a 'carrot and stick' approach to the telecoms operators, but it remains a mixed picture, particularly in more sparely populated areas.

A study published late last year by the consumer body Que Choisir considers there to be a ‘fracture numerique’ in the country, with around 7.5 million households (11% of the population) who lack access to broadband higher than 3Mbps, of whom three-quarters of a million have no access to fixed line internet at all.

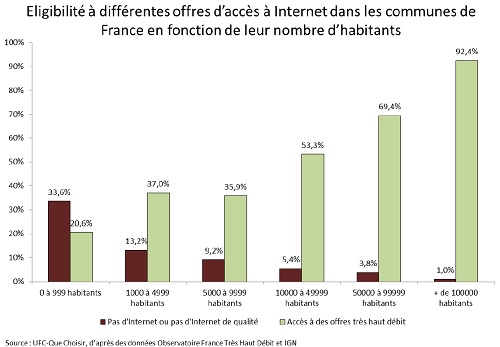

It showed that the smaller the number of inhabitants of a commune, the greater the probability that a high proportion of its population was likely to be deprived of decent access to the internet.

At the other end of the spectrum, there are municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants where internet quality problems remain relatively marginal.

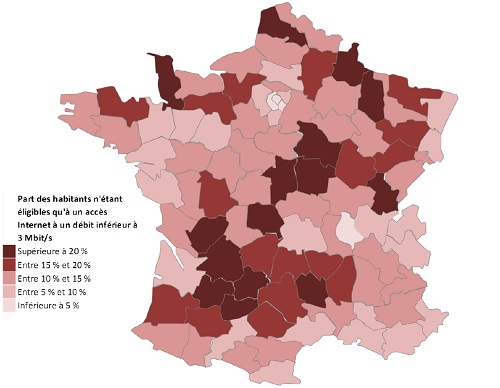

On a geographic basis, in 16 departments more than 20% of the inhabitants are not eligible for an offer with a speed of higher than 3 Mbps.

Those department whose inhabitants were the most deprived were Meuse (31.8%), Creuse (28.9%), Manche (26,2%), Lozère (26,0%), Yonne (24,9%), Lot (24,1%) , Jura (23,8%), Nièvre (22,6%), and Dordogne (22,5%), as can be seen from the following graphic.

The position is hardly a surprising one, for the technical and financial challenge of providing very-fast broadband in so many sparsely populated areas is huge, a position that is also reflected in most other European countries.

Emmanuel Macron has probably not helped matters by playing strongly on the misunderstanding of the terminology, with many households incorrectly assuming that his promise of "100 % de très haut débit" meant "100% fibre".

Only more recently has he accepted that different technologies are going to be have to be used to get the results, declaring that "il ne faut pas mentir aux gens. La fibre ne sera pas rapidement déployée jusqu'au dernier kilomètre, dans le dernier hameau."

As a result, for most households living in the countryside in France, in the immediate future any increase in bandwidth is being achieved either through upgrading the existing copper network currently used for ADSL (VDSL2), through terrestrial radio networks (such as Wimax and fixed 4G), or via satellite in those areas where neither hard wire or radio transmitters are available.

Although both VDSL2 and 4G are capable of très haut débit of 30Mpbs download, in many cases households are having to settle for less due to the technical and financial constraints that are inevitable in rural areas; there are distance limitations with VDSL2, and due to topography a 4G antenna may not always be within range.

In the longer term, most local councils have tentative plans for 100% fibre optic in their locality, but which stretch into 2030+.

Despite the difficulties with installing fibre optic in the countryside, the government is making strenuous efforts to meet the 8Mbps 'haut débit' minimum threshold for all households by 2020 and for fibre optic to 80% of households by 2022. By the end of this year an additional 3 million households should be able to obtain very-fast broadband.

To improve coverage in the countryside new radio frequency allocations are also been made to carry more 4G.

In addition, some procedural hurdles being encountered by the telecoms operators are being eased, with draft legislation currently winding its way through the French Parliament that shortens the planning procedures for the operators to put up new radio antennas (local councils themselves are causing some delays), and which also tweaks their powers to install new cabling on or over private property.

Conversely, it is also accompanied by the threat of increased sanctions on them if they fail to comply with authorisations granted on the deployment of fibre optic.

It is interesting to note that whilst there are 18 million households eligible to receive broadband of at least 30Mbps, less than half of them have signed up with an offer to take it.

As the monthly charge for subscribing to ultra-fast broadband is no higher than a good quality ADSL line, it is quite possible that for many households a lower bandwidth is enough to meet their needs.

Getting Information

The councils do not always excel in communicating the broadband service (DSL, cable, fibre, radio) that is available, so you may need to make relevant enquiries of the local councils to see what options are available to you.

In many rural areas departmental councils are subsidising the connection cost of a satellite or radio offer, so it is well worth making such enquiries.

A good starting point is to consult the interactive map provided at Observatoire France Très Haut Débit, from which it is possible to obtain the broadband speed available for a property, and how it can be obtained. It also provides an indication of the plan for the locality. However, such is the pace of development of the digital infrastructure that the map can never be fully up-to-date.

There is also a separate interactive map provided by Arcep, showing the deployment of fibre optic lines.

Most departmental councils (Conseil Général) also have good on-line information on broadband development, as do the prefectures. Many provide on-line interactive deployment maps you can consult.

Thank you for showing an interest in our News section.

Our News section is no longer being published although our catalogue of articles remains in place.

If you found our News useful, please have a look at France Insider, our subscription based News service with in-depth analysis, or our authoritative Guides to France.

If you require advice and assistance with the purchase of French property and moving to France, then take a look at the France Insider Property Clinic.